No one does video games for kids quite to the level of Nintendo. Their latest experiment, the Nintendo Labo kit, is a great take on blending the virtual and digital nature of video games with movements in the physical world.

Nintendo has a history of launching unique control schemes. For something like the Wii and its motion-tracking Wii-motes, they make it work by investing in their ideas with both the console itself1 as well as via top-notch first-party games. Though it can devolve into gimmicky territory—like the Wii-U’s controller-as-a-streaming-video-tablet—it often offers an alternative to standardized inputs and outputs in modern video game systems.

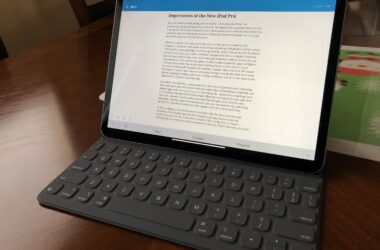

For the Nintendo Switch, the big feature is the console itself as a portable tablet, coupled with controllers called Joy-Cons that can be configured and used in a variety of ways. The Joy-Cons are tiny, but are built with additional hardware that adds motion tracking, infrared scanning, and a vibration system aptly named HD Rumble2. Their showcase for these features was a minigame collection at launch called 1-2 Switch, whose simplistic gameplay called into question the actual utility of all these hardware capabilities.

The Nintendo Labo is the next iteration of the Switch hardware showcase. At its core, it’s a bunch of cardboard, folded into accessories that hold the Switch’s main tablet and the Joy-Con controllers in certain positions to simulate real-world activities. Instead of just pointing a controller at the screen, a Joy-Con can be placed in cardboard box, attached to another cardboard box with rubber bands, and then act as a handle to detect hand motions.

Alternatively, a Joy-Con housed in a cardboard sleeve has its IR sensor pointing downwards at a bunch of other cardboard pieces with reflective tape, and reading how the tape moves gives the game enough information to play a music note or render a minigame.

The most striking aspect of this kit is, of course, the use of cardboard to build physical contraptions. Beyond the inspired use of recyclable materials, having the players build their accessories invokes a strong Ikea effect, and Nintendo leans into it further by encouraging customization. All of it only works because the Labo sets are meticulously designed, easy to build3 with thorough instructions, with an end-product that’s sturdier than it should be. Given that I had failed to engage my 5-year-old in pre-cut wooden models in the past, folding cardboard turns out to be much more accessible. It also doesn’t hurt that the completed widget can be played as a video game.

Which gets to the title of this post: the Labo is a good introduction to the playthings it draws from. Its minigames aren’t that interesting to most gamers, but they’re at the right level of complexity for young children. Labo’s manual assembly is a combination of Lego, origami, and has inspired a number of stapling-and-taping-paper-to-make-stuff projects. For older kids, there’s even an entire section trying to teach players aspects of programming and tying it back to Joy-Con functionality4.

Nintendo Labo is a hard game to recommend generally. It’s not that the concept is bad—the execution screams “Nintendo” with charm and whimsy—but much of this initiative is targeted at children, with some extras for truly creative folks to hack and piece together. For everyone else, once the novelty factor of building your own accessories wears off, Labo isn’t deep enough, nor its creation tools accessible enough, to procure much staying power.

Other console makers, in comparison, bifurcate their user bases by releasing separate accessories and then further sabotage their own efforts by mildly supporting these peripherals.↩

Which was predicted, before launch, to be dead on arrival. ↩

But the biggest sets still take a while.↩

And as expected, the internet has taken that functionality to its logical extremes.↩