About 15 years ago, giant boxes of peripherals stacked the shelves of gaming retail stores, filled with plastic guitars and copies of the then-experimental Guitar Hero games. At the time, the genre was fresh and exciting, and music games garnered enough popularity to briefly cross into the mainstream, when bars would actually hold Guitar Hero competitions in lieu of booking live bands. Guitar Hero—and its eventual competitor Rock Band— ended up each spawning multiple sequels, incorporating additional instruments such drum kits, and adding vocals as a karaoke-lite option down the line1. As companies rushed to convert as much music as they can into video game-form, they quickly saturated the market with rhythm games with little variance outside of their soundtracks, and the genre ran out of steam within a couple of years of that initial experiment. Plastic guitars now mostly take up residence in closets and landfills.

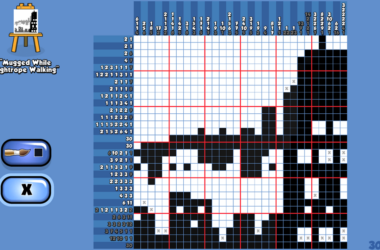

That was the American experience of rhythm video games. In Asia, musical rhythm games started as a niche genre and stayed niche for over two decades; the most popular series is probably Konami’s Bemani franchise, encompassing everything from Beatmania IIDX (DJ/pianoing) to Dance Dance Revolution (dancing/rhythmic stepping) to Jubeat (telephone switchboard). Occasionally, arcade and home console game releases in the US serve as a periodic reminder that there’s a core group of dedicated gamers who still enjoy pressing a bunch of buttons in quick successive sequence.

To be clear, these games coming out of Taiwan, Japan and South Korea aren’t radically reinventing the rhythm genre either; there have been a handful of control scheme gimmicks, but the longest running series—DDR, Beatmania IIDX, DJMax—have kept their basic gameplay elements the same this entire time. I’d say that the biggest difference between the Asian and American approaches to the genre is that while American game studios quickly went through their catalog of pop and rock songs of the past 30 years, the Asian approach focused on a set of musical genres: namely J-Pop, K-Pop, electronica, techno, and some of their close musical derivatives and remixes. In particular, the Asian music games employ artists and DJs to make new songs for each game, so each release has the added appeal of music discovery.

The other notable difference is the difficulty of this Asian rhythm game subgenre. That is not to say that Guitar Hero can’t be hard; people are still finding ways to ever more perfect some of its infamously blister-inducing songs. Rather, given there have been so many sequels of popular rhythm games, its developers continue pushing up the skill ceiling with every iteration, in doing so keeping their franchise even more esoteric and niche. These games are made by the dedicated for the dedicated.

Whereas musical instruments offer the inherent satisfaction of playing music with melody and tune, rhythm games have a much more direct feedback mechanism: timing judgement in real-time, electronic notes mostly corresponding to the underlying musical notes2, and an ongoing streak count that serves as motivation to keep the music flowing. It’s hard to fully describe the appeal, but the closest analog might be getting absorbed into a piano visualizer, a cascade of notes and particle effects in rhythm with sound.

I’ve been playing rhythm games for quite some time, starting with early versions of Beatmania IIDX with a Rock Band stint with my roommates3 and nowadays mostly via the Switch and iPad. My reflexes certainly aren’t what they used to be, and I have less time to play or practice now than before. For me, these games are less about the music or even achieving high scores.

Rather, I’m at my best when I’m losing myself to a state of focus and raw reaction, akin to entering a flow state—just with strobing lights and flashing combo scores.