I’m a personal finance geek. Starting with Mint and their budgeting tools and having moved on to Personal Capital for their investment tracking

As I’m accumulating more assets from building upon my career, I’ve shifted from divvying up paychecks for expenses to having to formulate a medium-to-long term financial strategy for myself and my family, but this transition is trickier than I had anticipated. Some forums, like Reddit’s /r/personalfinance, provide strategies to pay off debt or reconcile budgets; other forums like Bogleheads exist for members to discuss in-depth investment strategies.

But as far as I can to tell, there isn’t a comparable community or support for coming up with an overarching financial strategy, one that would encompass retirement, investments, and income and expenses. The closest approximation has been asking for advice from a number of Certified Financial Planners—from the likes of Scottrade, Betterment, and Personal Capital—who are happy to dilvuge their experiences if I take part in their portfolio management services, to the tune of 100–200 basis points.

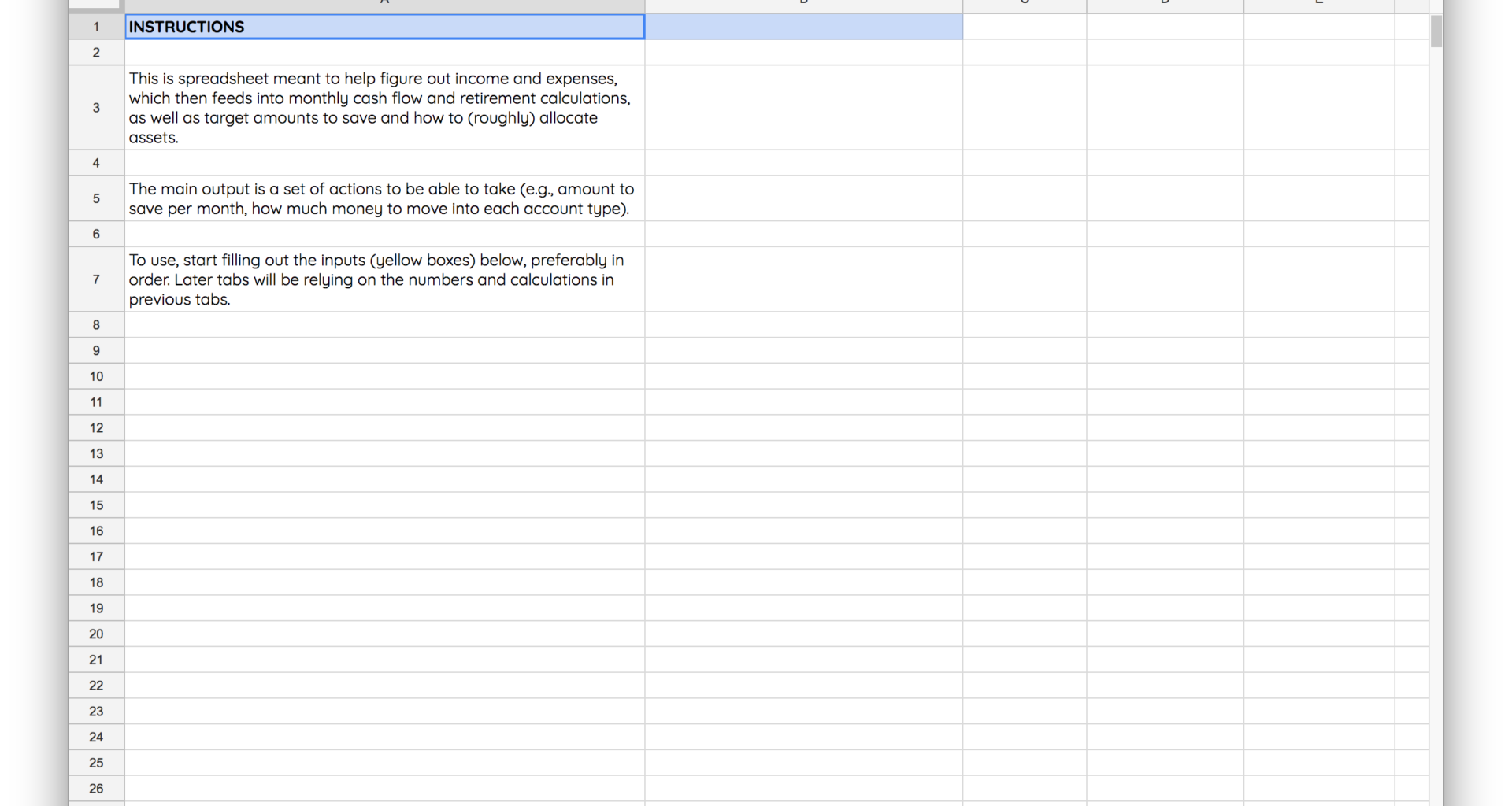

So instead of paying a reoccurring cost for singular pieces of advice, I put together their findings (plus my own observations) into a simple spreadsheet. I’m sharing it here:

Financial Overview & Planning (Public)

(the link here will make a copy in your own Google Drive and tweak the numbers and formulas to your own situation)

Read on if you’re interested in my thoughts and philosophies in coming up with this financial model.

Define Inputs and Outputs

The first order of business is to figure out what numbers go in, and what you want to get out of this exercise; in other words, inputs and outputs.

The inputs are straight-forward: income, expenses, plus financial accounts’ holdings.

Outputs are more varied. Programs such as financial independence look for sum amount of money that could sustain a lifestyle, and retirement calculators solve for the minimum amount to save for a comfortable retirement. Meanwhile, budgets concentrate on expense reduction, and investment models boil down to variations on compound interest formulas of the principal*(return rate)^n variety.

The output I’m interested in is simple: how much should I save each month, where should that money go, and when can I retire1 following this plan? This allows me adjust numbers that have projected effects decades away, although I’d be the first to acknowledge that this is an imprecise art.

Assume the Worst

All forecasts are pseudo-educated, simplified guesses on what may happen in the future. The magnitude of the variables and what you plug into the formulas makes a major difference in outcomes 10–20 years down the line, especially with compound interest.

I prefer more a more conservative outlook in my spreadsheet and use it to establish a financial baseline. It’s why, out of the 10/50/90 Monte Carlo simulation percentiles, I’m most interested in the 10th percentile outcome; what matters is whether my amassed savings can ride out the bad times. Similarly, while historical return rates of the S&P 500 are estimated around 10% annually, I use the lower—and easily explained—model favored by Warren Buffett, which pegs return rates at only 3–4% after factoring in inflation.

Put Some Slack in your Budget

It sounds oxymoronic, but I like the idea of creating and mostly adhering to a budget.

Like the act of putting words to a page, I find the process of budgeting cathartic and helpful in disclosing where money goes. With online tools available to suck in data from banks and credit cards and investment accounts, categorical expense tracking is mostly automated. If nothing else, it just feels responsible to pour over pie charts detailing mortgage escrow activity.

While there are those that recommend accounting for every single dollar of spending, I only want to apply that level of discipline when trying to pay down small pockets of debt2. Instead, I generally want to come up with a rough idea of reoccurring monthly costs—which includes retirement savings as a “cost”—then reverse engineer a reasonable amount to save from what’s left.

Monthly disposable income, then, is the small amount of money left after expenses and savings. Having a little extra spend for impulse purchases makes budgeting more tolerable; I’d be less inclined to maintain it if strict adherence was the only method of implementation.

Buckets of Capital

Keeping around 3–6 months of expenses as an emergency fund is a common personal finance best practice. Extending that same concept outwards to additional sets of capital, though, was not something that had occurred to me until a financial advisor mentioned the structure. Specifically, he verified that it’s the structure his clients employ with an eye towards financial independence, and involves dividing up money into areas which are either less liquid or increasingly volatile, drawing from their accounts in that order.

For me, it stacks up like this:

- 9 months of expenses, in cash, parked in high-yield online savings accounts

- 10–20% of remaining capital in cash-generating funds (e.g., REITs), which can be tapped if the emergency fund runs out

- 80–90% in low-cost index funds, ETFs, individual stocks, etc.

- One-off real estate investments

The idea is to exhaust each layer of capital before moving to the next, and the relative liquidity of each layer makes it progressively harder to tap. At the same time, the upper layers act as a buffer for market fluctuations, riding out downturns. With this setup, the typical advice around what to invest in applies primarily to that third pool of capital, and I’ve personally had good luck with keeping that money sacrosanct3.

Acknowledge the Futility of Planning

I wish someone had fully impressed on me that financial plans are fickle. Every investment comes with a standard “past performance doesn’t guarantee future returns”, but the disclaimer is presented with a wink and nod; of course you’re looking at history to estimate future performance. I had a CFP print out a 30-page booklet, customized to my financial situation that, after spending an hour going over the fine-grained details with me, became obsolete within 3 months.

All of this is to say that the numbers may have some validity in the short run, but financial planning requires diligence and constant re-evaluation of circumstances. As much work as there is that goes into these predictions, they’re only as accurate as the next time your finances are revised.

Here, my idea of retirement is the gentler “don’t have to work, but it keeps me busy and provides meaning” variation.↩

For instance, I had a student and car loan coming out of school, and every paycheck was a priori divided into spending buckets.↩

The one time I had to sell off stocks was to make the down payment for our current house. Mortgages, especially in the Bay Area, tend to wreck all financial planning.↩