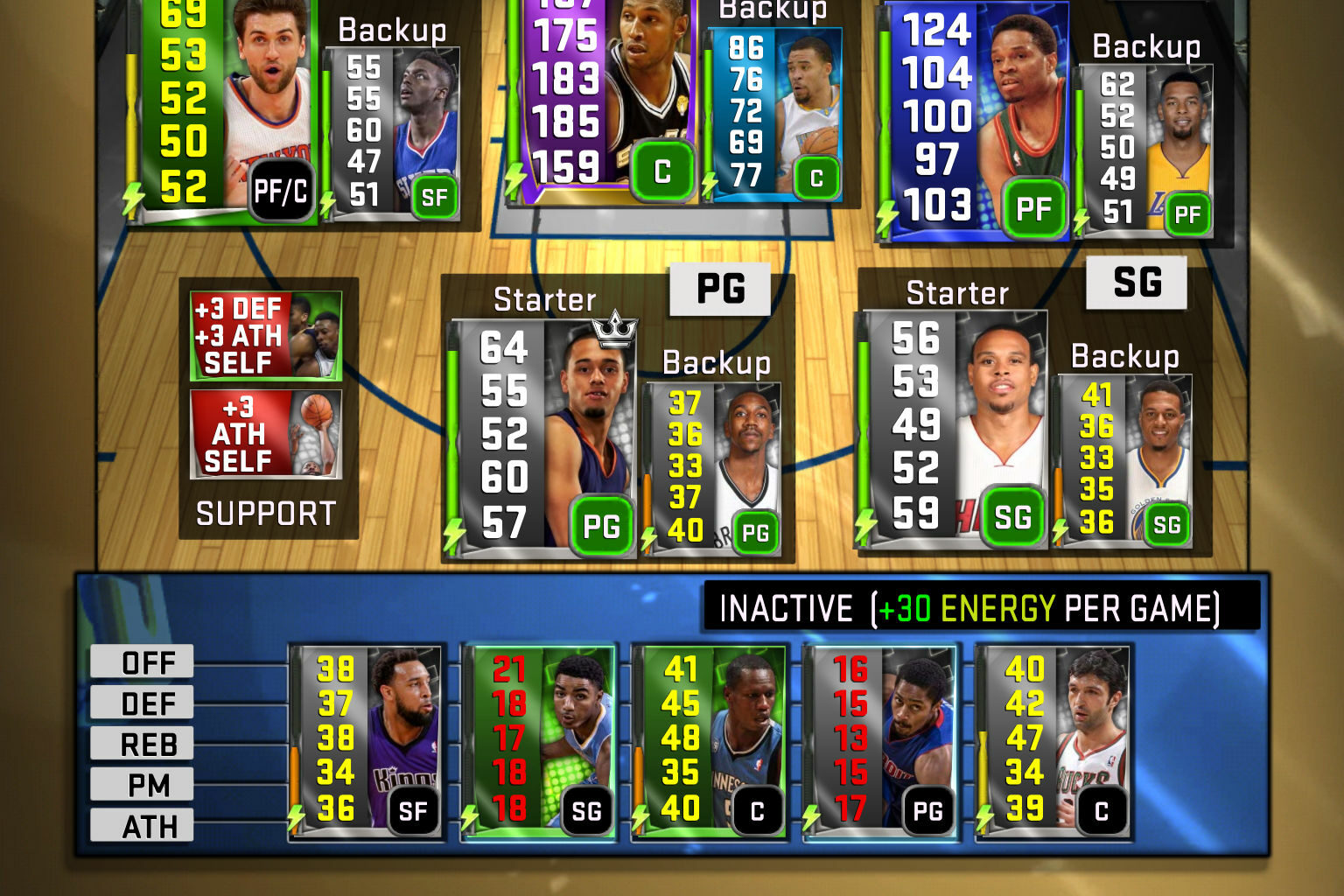

I’ve been slogging through My NBA 2k15 on my phone. The game is based on collecting cards to battle other players offline, and its core is identical to that of another game, WWE SuperCard. In fact, they simply reused their game engine, likely built for white-label collectable card games, and release new games by licensing brands and plugging in art assets.

Many have embraced the art of recycling game materials. Whether they’re reusing mechanics, artistic resources or game engines, small game developers have long understood how build with less; usually, by copying.

I remember doing the same a few years ago while working for a friend’s Facebook games company. It wasn’t our intention become a generic white-label game factory, but when we noticed that the same game mechanics persisted across many of the games in our space, we realized that it’d only take a few drops of extra engineering elbow grease to generalize this system. With small tweaks to balance gameplay and a new set of outsourced art plus a new story and copy, we were fairly successful in targeting new audiences with variations of the same game. It was a moderately successful strategy for a time, shortening development cycles from quarters to weeks.

Contrast how these games work compared to that of the biggest AAA titles.

In today’s gaming landscape, the most expensive games take a huge amount of effort to build. From the initial stages of ideation all the way to finalizing the gold master, they have budgets that shoot into the tens of millions, teams of hundreds, with project roadmaps that take years to complete. It took an estimated 5-6 developers six months to build the iconic Super Mario Bros. 30 years ago; the latest evolution of that game – New Super Mario Bros. U – took a much larger team upwards of three years to develop.

At some point, this expansion of development time, cost and effort has outpaced the growth of the industry. Meanwhile, the prices of games have resisted expansion, and beyond moving to a standard price of $60 a few years ago1, developers have had to make up the difference largely by volume. Unfortunately, this strategy is not effective for many top games, and they find themselves dropping prices weeks after launch to try to boost sales and maintain interest2.

Can our biggest games sustain this type of development? The MMORPG genre has come and gone; the ballooning time and cost to build a massive online RPG has made it an infeasible category of games to build. Today’s Call of Duties and Assassin’s Creeds are likely heading towards the same endgame.

Which, when adjusted for inflation, costs less than new $50 games just a decade ago.↩

Particularly when their selling points require active and robust multiplayer communities.↩